Stripes for Days - Retake

- Ashley Webb

- Jun 14, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 17, 2020

When I mapped out May’s blog posts, I accidentally chose a photograph and a dress with a very similar color scheme: blue stripes. Of course, the dresses have very different uses – one being a nurses uniform, and the other being a light summer dress, but by the time I realized the similarity, I had already done the research on the photograph and mounted and photographed the dress, as well as conducted an initial outline of the blog post. In the end though, I did have a chance to choose a different dress and save the blue stripes for a different month, as the draft I had written on the dress was deleted somehow on my blog hosting site, never to be recovered (hence May’s post in June). And because I believe whole heartedly in Newt Scamander’s philosophy that worrying means you suffer twice, I chose to forget it, and recreate the post (this time in Word) at a slightly later date.

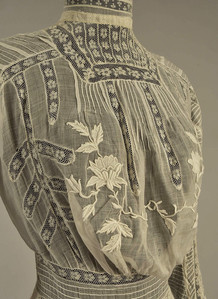

When I found this 1900-1903 cotton dress several years ago, I thought it charming. It’s an interesting study piece, but in my own study of it, I have to admit, I was slightly bamboozled by it. I first thought it was a theatrical reproduction – mainly based off certain flaws in its construction, making it somewhat of an anomaly in terms of the quality associated with many turn-of-the-century dresses (the 20th century, that is). The craftsmanship is there, in some areas more than others, but it lacks finesse. Mounting it helped, and ultimately swayed my thinking away from it being a reproduction. The lay of the pigeon bodice was one of the reasons that I initially thought it a theatrical piece.

What is a pigeon bodice you ask?

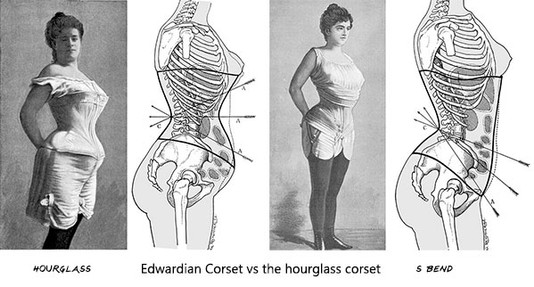

Aptly named after the pouter pigeon, these bodices were tight across the back, and fluffed out at the bust to the waist, thanks to a little help from some specialized undergarments, giving the wearer a pigeon-like look. The Edwardian silhouette, created from an S-shaped corset, enhanced this figure, creating a mono-bosom to hide the exact position of the waist by pushing the bust forward and the hips back. Of course, fashion plates exaggerate this, but this Edwardian ideal of beauty appeared heavily for about a decade, from around 1898 to about 1907.

Pastels, ruffles, and lace added to the silhouette, bringing a touch of femininity back into the style, a change from the dark colors, heavily bustled dresses, and even the masculine New Woman dresses of a few years before. The emphasis was still on the waist, but instead of an exaggerated shoulder line, seen in the early to mid 1890s which intentionally illuminated the small circumference of the waist between the massive gigot sleeves and the corseted and petticoated hips, the bust played a larger role.

The S-bend corset aided in this by having a straight front, there-in pushing the hips backward. The bust was left exposed above the corset, and with the help of certain types of camisoles and corset covers, the pigeon bodice could be filled out to match the desired silhouette.

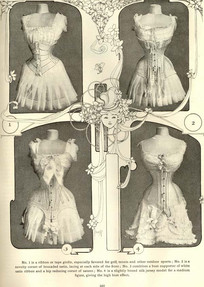

One historic costumer even did a test with some Edwardian undergarments on a mannequin under a shirtwaist. The photographs below show how the close the silhouette could be achieved with the aid of certain types of bust enhancers. These bust enhancers are a real thing, and can be found in museum collections - I promise I'm not making it up!

Unfortunately, this isn’t the case with my bodice. The interior cotton bodice, while leaving room between the striped cotton fabric and the waist lining to give the illusion of the pigeon, it meets the cotton fabric just below the bust, and is pulled tight: there is no additional room to enhance the bust with any sort of extra frilliness – even in a corset cover or camisole. The type of hook and eye system, along with sewing techniques attaching the hook to the lining was perplexing.

The hook and eyes had me questioning its authenticity. The hooks from the bust to the waist are unique, in that they have a locking system to keep the hook from falling out of the eye. Once in, they’re extremely difficult to get back out. I haven’t seen anything historic like these previously, and the way they’re hastily sewn to the lining is odd.

However, the size of the waist and the construction of the bodice itself made me reconsider. Sitting at 20.5 inches, this means the person’s actual waist size would need to be around 20 inches or less in order to give enough room for the chemise, bloomers, corset, corset cover, and petticoat. This is probably the tiniest waist I’ve encountered other than in child’s clothing! The bust is roughly 29 inches, which may mean this dress was made for a teenager or a slight woman in her early 20s.

The construction of the garment in itself is interesting in a number of ways. It follows the typical construction of bodices throughout the 1850s -early 1900s, being comprised of four panels to fit the garment across the back and tapering to the waist. At the waist, both front and back, the fabric has been gathered and then hand sewn to create the fullness without compromising the fabric. Plus, it allowed for the potential to let the material out at the waist as the woman grew, if it in fact was a teenager’s summer dress.

Another interesting aspect to the bodice is the ruffled yoke. It’s not quite a separate piece, but hides the hook and eyes at the bust. The yoke hooks at the shoulder seem via hook and loop closures.

Detail of hook and loops

The ruffles on the yoke were created from the same fabric as the rest of the outfit by bunching the fabric along the white lines and then sewing and then oh-so-delicately sewing on the inside edge of the line. There’s a lot of potential to go wrong, at least, that would be in my case, as I’m an awful seamstress. This is the same on the little cap sleeve details at the shoulders.

Unfortunately, there is some damage to both the bodice and the skirt. The lining is ripped fairly heavily at the waist, as if someone tried to put it on a modern mannequin and attempted to hook it closed. There is some light damage to the right proper sleeve, and the waistband to the skirt is completely gone, as if it had been ripped off.

The skirt is typical for this time period, with six panels; however, the waist fabric is much wider than a woman with a 20.5 inch waist should be. There is no train, which was typical at this time, but the upper tier of ruffles rises at the sides, giving the illusion of a longer and flowing figure.

Comments