1887-1889 Velvet Capelet

- Ashley Webb

- Jan 20, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 2, 2021

The winter is in full swing here in Virginia, and all I've wanted to do is wrap up in something warm. It's always cold in museums, so I figured a nice capelet would be a good winter feature.

If you'd prefer to ingest this information via video, here it is! If not, keep reading below the video.

Eons ago, I posted in my Instagram that I was working on a blog post for this piece, but life got in the way, winter quickly morphed into spring, and I felt it wasn't the right time to release a more in depth unboxing of this piece. But, now it's out of storage, it's been living in my library for about six months, and I'm so excited to share with you all of the elegance and beautiful understated-ness of this c. 1887-1889 velvet capelet.

This piece was a little hard to date, as this style of cape wasn't extremely popular. It shows up in fashion plates every now and then with a similar one-off example, but most extant capelets from this time period of similar construction were either covered in beading or had fringed sections for the arms.

Most of the outerwear in the 1880s were longer and polonaise style. Which means the cape was nipped in at the waist and a sort of an overskirt that flowed over the back of the bustle.

I know it wasn’t popular at the time, but I almost prefer this understated, elegant style instead of the ostentatious and over the top beading and fringe that was so popular the in the 1870s and 1880s. There’s just something about it that just makes it classic. I think the slight puff at the shoulders is what does it for me. These date to the later 1880s – just before the rise of the Italian shoulders and then the gigot sleeves of the mid 1890s.

On the inside, it’s lined with a lovely deep purple silk, and it’s in amazing condition. There’s a few spots where the weft has remained and the warp has worn through, but that luckily gives us a chance to peek inside. The silk hasn’t shattered at all, which is surprising considering its age, and the potential dyes that were used to make that deep purple color. You can tell that it was worn and loved, but whoever owned it took extremely good care of it.

In terms of construction, this garment is essentially 3 layers – the velvet outer layer, the felted wool interfacing, and then the silk lining. It’s made of four pieces: the two front lapels that attached at the shoulder, with the seams running down the front of the garment, essentially following the line of the arm.

The collar is a separate piece, and for some reason the lining of the collar, cut on the bias, is two pieces combined at the center.

The back of the garment and the shoulders are all one piece, and they used a thick silk thread to whip stitch the shoulder seams into place. The seam starts at the shoulder blade, was gathered at shoulders to get this nice pleating, and then attached to the front panels.

Everything is then nicely tucked in and whip stitch or fell stitched together so no seams are visible. Large hook and eye closures run up the length of the bodice front, about an inch and a quarter apart (or 3.175 centimeters for all of my European friends). These of course were sewn on before the lining was attached, so all of the threads are hidden.

There’s even a lovely little 3/4ths of an inch (or 2.54 centimeter) panel running up the eye side, so if one hook did happen to come undone - which was probably unlikely looking at the design of the hooks - but if it did, you wouldn’t see the bodice underneath. This panel was attached last with a fell stitch – the black silk threads can be easily seen.

There is a tag, and unfortunately, the company's history is a sad one. This piece was sold by Cincinnati furrier and retailer A. E. Burkhardt, a major men's cloak and coat retailer from the 1860s up until the 1990s.

Adam Edward Burkhardt was a German emigrant to Cincinnati in 1853. In 1859, he became an errand boy for Cincinnati furniture company Mitchell & Rammelsburg. Three months into this position, he decided his salary was too low at a dollar per week, and took employment under Jacob Theis - retail hatter and furrier. In 1866, Burkhardt bought out Theis' business, and with his brother-in-law, renamed his raw fur importing business The Burkhart Brothers. At some point between 1867 and 1875, A. E. assumed sole responsibility of the company and renamed it A.E. Bukhardt & Co.

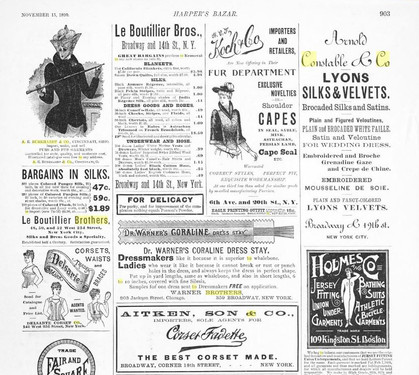

By 1875, Burkhardt had two retail stores in Cincinnati, and was on top of the world. He had married Emma Erkenbrecher in 1871 - the daughter of successful starch merchant and founder of the Cincinnati Zoo. He imported raw furs from several continents, and was coined the 'pioneer fur merchant of the west.' In 1886, A.E. Burkholdt & Co. opened a new seven story retail location that the Cincinnati Post coined 'the most palatial mercantile structure in the world.' Ads for women's and men's cloaks appeared in Harper's Bazaar, and the company took full page ads out of Cincinnati's newspapers.

One year later, Burkhardt commissioned Samuel Hannaford to design and construct a rock-faced Victorian home at the outskirts of Avondale, Cincinnati. Unfortunately, Burkhardt's luck seemed to run out by 1890. In 1891, the seven floor retail location burned to the ground. Burkhardt borrowed $1600 from two employees to try and keep the company afloat, but with the Panic of 1893, the company was on the verge of bankruptcy. Burkhardt sold his shares in the company in 1892, but remained President until December of 1895. In 1896, the individual that had the most shares of the company was advised to sell everything at public auction.

Around the same time, the Burkhardts divorced, dividing allegiances between their five children. Perhaps the loss of the company and the family's diminishing wealth led to the rift that caused the divorce. The rift between the family was so bad that Emma declared herself a widow in the 1900 census, even though the A.E. was very much alive, and even living in the same city.

When the company went for public auction in 1896, she borrowed $15,500 and put her jewelry down as collateral. She purchased all the property and assets of the A. E. Burkhardt Co., to include all the merchandise, store fixtures, the delivery wagon, and the lease. After re-establishing the company in 1896, renaming it Burkhardt Bros, she passed it to two of her sons - Andreas and Carl.

Ever resourceful, A.E. began another hatter and furrier business, calling it the A. E. Burkhardt Hat and Fur Co. The same year, Emma sued A. E., claiming his use of such a similar name to his previous company and an extremely similar trademark were illegal, as all branding and trademarks, including the use of the name 'Burkhardt' were transferred into her care upon the purchase of the company and all its assets. She won the case, and Burkhardt Bros., which outfitted men in hats, ties, coats, and other necessities lasted well until the 1990s.

Most likely prior to the couple's divorce, Burkhardt accepted the position of President of the Cincinnati Zoo, offered to him by his father-in-law, and brought it from the brink of collapse. This position most likely helped A.E. financially, not only after selling the Burkhardt company in 1892, but the court case in 1897, as well as the less than adequate sale of their 33-room mansion in 1902. Burkhardt remained president of the zoo until his death in 1917.

Fences were never mended between husband, wife, and children, however, and A.E. and Webster are buried in a different family plot than Emma, Andreas, Carl, and Beatrice - all in the same Spring Grove Cincinnati cemetery (their son Cornelius took a neutral position, and is buried with his wife's family within the same cemetery.)

Because of the various stores, brands, and family complications, it was hard to date this tag without doing research on styles and fashion plates from the time. There are at least three known labels - the label currently inside the capelet discussed above, a label consisting of a coat of arms, and a label used in 1892 at the sale of the company including a lion resting on a platform along with the words 'Arbiter of Fashion.' Regardless of the company's 20th century history, we can definitely say this cape is pre-1895 based on the tag alone, as the sale of the company transferred the title and trademark to Emma Burkhardt in 1896.

The only reason I can think that this label is less elaborate than some of the others, is that perhaps with the multiple locations, a more generic tag would need to be used. Additionally, maybe the lion and crest were seen as too masculine, and with the introduction of the seven floor retail location, branching into women's clothing (and therefore a change in tag) was a necessary addition.

So, I wanted to try and have a pdf of the pattern with this post, but I got involved with other things, deadlines loomed, and I never got a scaled pattern done. I hope that eventually I'll be able to get one to whoever may want to use it. I wear my capelet all the time around the house :) It's super warm on the shoulders!

Comments